Introduction

David H. Hanes of Erie Pennsylvania was our special guest speaker for the March 2017 meeting. This member since 2002 offered three 45-minute lectures over the weekend on a musket that had belonged to a member of a Pennsylvania militia unit that guarded Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry’s Erie shipyards during construction of his American fleet in 1813. Members enjoyed hearing the story of the only known regimental-marked militia musket with a proven connection to the Battle of Lake Erie. The presentation was free and members were encouraged to bring guests. In addition, David will bring back his award-winning 2016 Annual Display Show exhibit “A Well Regulated Militia…In Defense of Perry’s Fleet” which can be viewed throughout the meeting in the center of the hall against the wall.

David Hanes

Background

Unlike our British opponents, the firearms with which we fought and won the American Revolution (1775-1783) were anything but uniform. The standard British land force weapons were the 0.75 caliber Long Land and Short Land Pat- tern “Brown Bess” muskets. American combatants, on the other hand, brought whatever they could to the fray. There was no national armory from which to produce nor arsenal from which to draw standardized military grade weapons, indeed, throughout the American Revolutionary War, American martial firearms came from various sources: personal weapons, raids on British arsenals, confiscation from Tories, a variety of European arms, commissioned “Committee of Safety” muskets, and battlefield pickups. The arms situation changed dramatically, however, when the French began supplying firearms, at first surreptitiously, then openly after 1777. This arm was their 0.69 caliber Model 1763 (and its later variants) “Charleville.” During the course of the war the French would supply many thousands of these arms to Americans, thereby not only effecting the final outcome, but influencing American martial firearms design for decades to come.

In the John Trumbull painting The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton, January 3, 1777 no American firearms are depicted. Rather, Americans are shown fighting with swords alone and will presumably arm themselves with muskets of the fallen British after Washington saves the day. Why Trumbull chose to depict Americans without firearms is a curiosity. Perhaps in the postbellum era Trumbull felt it important to memorialize the arms disparity between combatants, or perhaps he meant it as a reminder that we were still woefully unequipped and dependent on foreign nations for firepower. In any event, Trumbull captured the essence of one common fighting tactic born of necessity: hand to hand combat, sans firearms.

Between the American Revolution (1775-1783) and the War of 1812 weapons carried by the troops became more standardized. Above painting of the American Revolution by Archibald M. Willard, ca 1876.

Martial Gun Manufacturing Begins in the US

The year 1793, ten years after the end of the American Revolutionary War ended, would find the French embroiled in a revolution of their own and again at war with England. Secretary of War Henry Knox assessed the arms situation and what he found was not good. Precious few arms were found suitable for service, and these included a mixture of French and British muskets and therefore not of uniform caliber, a critical consideration in the logistics of war.

Further, the 1790’s would usher in the beginning of the American two-party system. The pro-British Hamiltonian Federalists would rise to power over the French-leaning Jeffersonian Republicans. This internal power struggle in America begged the question with regard to martial firearms: If we are to rely on a European supplier of firearms, from whom would we obtain those firearms? As it turned out, instead of an ally, the US would almost go to war with France in the so-called Quasi-War (1798-1800). At the same time, the British government would refuse to allow Ketland, a major firearms manufactory, to fulfill a 10,000 arms contract with the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Considering the condemnable state of arms and perhaps anticipating our political dilemma with regard to European alliances, in 1794 Congress approved the construction of two federal armories for the purpose of manufacturing small arms. The locations chosen were the already existing Springfield, Massachusetts arsenal and Harpers Ferry, Virginia, the latter location chosen presumably to be nearer Washington, DC. These armories began production in 1795 and 1800, respectively.

Because our national defense was still heavily dependent upon militia, and because the nascent federal armory system was not yet fully operational, parallel arms procurement measures were taken. Most notably, the United States government along with the Commonwealths of Virginia and Pennsylvania procured arms from alternate sources. In 1794 and 1798 contracts, the U.S. government solicited nearly thirty private gunmakers to manufacture approximately 47,000 arms (of which perhaps one-half were ever made).

In Virginia’s 1797 legislative act, Virginia authorized the construction of their own state armory at Richmond and also secured arms from several private contractors. Private contractors also supplied arms to other states and for individual sales. All of the armory and contract muskets in this period, variances among manufacturers notwithstanding, are of the period-termed “Charleville Pattern” or “Charleville Musket” design.

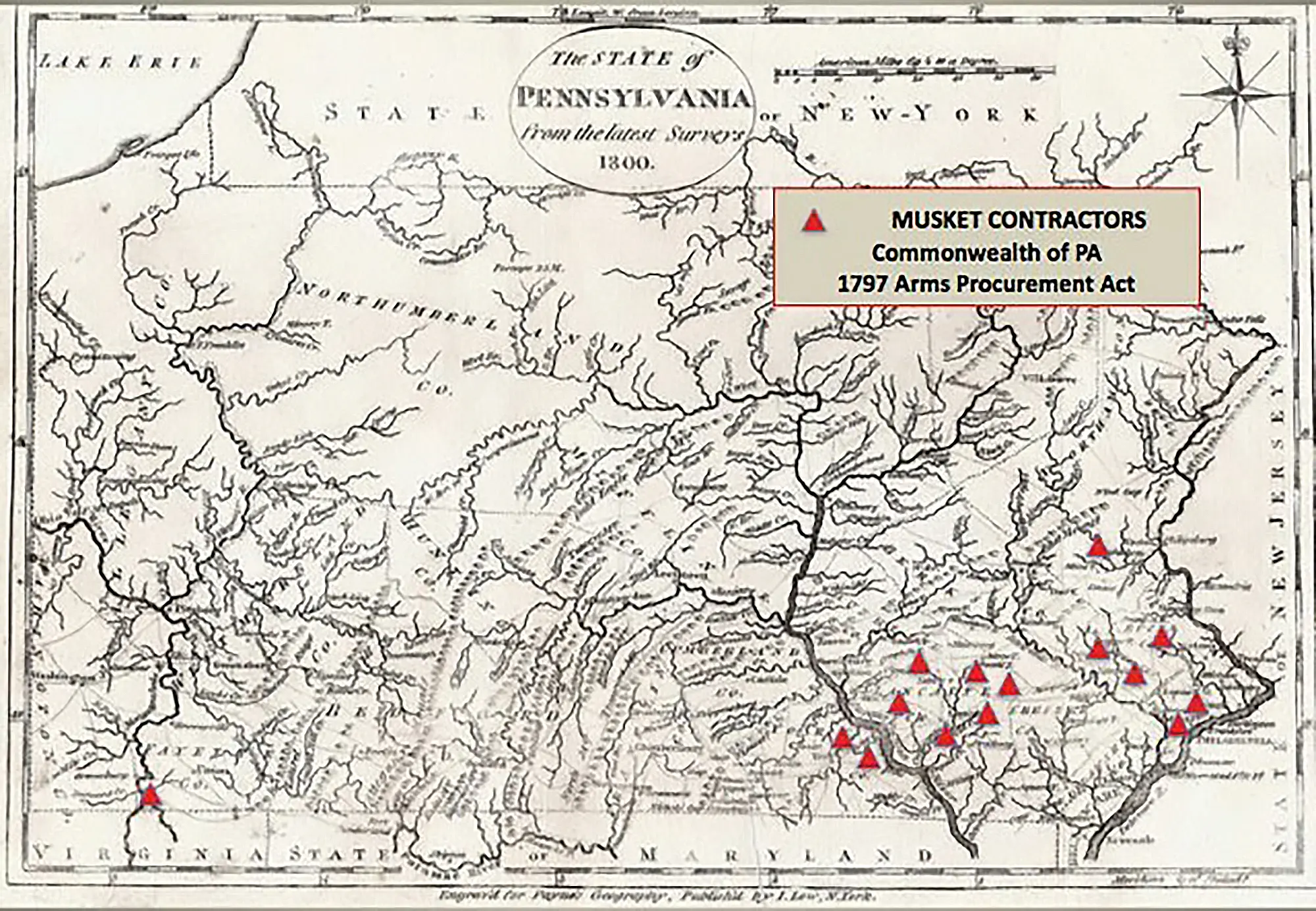

Pennsylvania Militia Muskets

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Arms Procurement Act of 1797 authorized the procurement of 20,000 muskets, of which 19,900 were contracted to fifteen gunmakers, all in Pennsylvania. As mentioned previously, an order for 10,000 muskets was initially awarded to Ketland, but the British government correctly predicted that no good could come from that and squashed the deal. The order was subsequently distributed to other Pennsylvania gun manufacturers.

Musket Contractors Commonwealth of PA 1797 Arms Procurement Act

The list of Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (CP) contractors is shown in the table on the right, the left side being the original contractors, the right side being the replacement contractors for the cancelled British order. To the perceptive eye, this list will reveal two peculiarities with one of the contractors. First, the contractor himself: Albert Gallatin was the only non-gunmaker to earn an arms contract. Second, the county where Gallatin’s guns were made: Fayette County, south of Pittsburgh near the Virginia (now West Virginia) state line, is primarily a wilderness circa 1800. Fayette County is the only site listed lying west of the Alleghenies, the others are all clustered about the traditional gun making region of Southeast Pennsylvania. So, to what can we attribute these anomalies?

Musket Contractors 1797 Arms Procurement Act

Albert Gallatin

To tell the Albert Gallatin story let us first retrace Lewis and Clark’s adventure up the Missouri River to Western Montana. Our journey would reveal what the Corp of Discovery found in 1805: At one point the Missouri River splits into three forks, all roughly the same size, and clearly none large enough to provide the North- west Passage that they hoped to find. Concluding that the Missouri River effectively ended here, they named the three forks: the Jefferson, for the President and sire of their adventure; the Madison, after the Secretary of State; and the Gallatin. So, who was Albert Gallatin, and what role did he play in securing an arms contract in Western Pennsylvania?

Today, the Swiss-born Albert Gallatin (1761-1849) is perhaps one of the lesser known of our founding fathers, but he served an eclectic career in both public and private service. A short list of his accomplishments includes: U.S. Senator from Pennsylvania (1793-94); U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania’s 12th District (1795-1801); Secretary of Treasury (1801- 814) under Jefferson and Madison, becoming the longest serving Secretary of the treasury in our nation’s history; Ambassador to both France (1816-1823) and Great Britain (1826-27); co-founder of New York University; president of the National Bank in New York City; and his career-long study of Native American language and culture led to his founding of the American Ethnological Society, earning him the sobriquet “the father of American ethnology.”

Albert Gallatin also established the town of New Geneva near where the Monongahela and Cheat Rivers join in Southwestern Pennsylvania, just a few miles north of the present West Virginia line. Gallatin wanted to establish a community for expatriated French who were escaping the ravages of the French Revolution. His estate, Friendship Hill, now a National Historical Site, lies about 25 miles from Fort Necessity. During Congressman Gallatin’s tenure he was awarded a contract to build muskets under the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Arms Procurement Act of 1797 (q.v.). Not a gunmaker himself, he subcontracted to Melchor Baker, a gunmaker in his district, in the New Geneva area. This apparent conflict of interest would not have been considered improper for the time and so was not questioned.

The Melchor Baker Musket

Melchor Baker produced at least 1200 guns for the Gallatin contract. An educated estimate among CP musket col- lectors is there are perhaps ten of the Baker muskets extant. The musket de- scribed herein is one of those 1200. This musket bears strong resemblance to the Charleville pattern, and along with the barrel proof mark of a Liberty Cap over a ‘P’, indicates it was an early CP. Later manufacturers of CP’s would follow Springfield’s lead in changing to an eagle head proof mark and also by eliminating some of the stylistic features (e.g., hammer spur and flash pan curls). The lock plate is stamped “M:Baker”, “CP” stamps appear on both the lock plate and barrel per Pennsylvania contract specifications, and the “T” inspection mark, deeply struck on the left side of the stock near the side plate indicates a known inspector, Joseph Torrence, inspected the musket prior to 1802.

Lock plate stamped with “M:Baker” and “CP”

“T” inspection mark, deeply struck on the left side of the stock near the side plate indicates a known inspector, Joseph Torrence

The stock has a prominent “133” on the right side indicating 133rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment, and a “44” is stamped on the top of the stock near the butt plate. The modified 1816-style bayonet also has a “44” stamped on the socket. The muzzle of the gun has been filed down to accommodate the later model bayonet, and while the bayonet is not original to the gun, it appears the two were fitted and match-marked later, but during their period of use.

Forming the Pennsylvania Militia Regiments

In 1807 the Pennsylvania Militia Act, “An Act for the Regulation of the Militia of the Commonwealth,” took the 131 existing independent state militia regiments, added a few more, then organized them into sixteen divisions. The Sixteenth Division was formed from seven burgeoning northwestern counties (Beaver, Butler, Crawford, Erie, Mercer, Venango and Warren) and included eight militia regiments numbered 132 thru 139. The 133rd Regiment was one of eight regiments in this division, consisting primarily of volunteers from Crawford County. While this area of Pennsylvania was still mostly wilderness, until the War of 1812 there was little threat from Native Americans or the British, so no noteworthy activity occurred for the first several years after the formation of the division. This, however, would change in 1813.

Perry Builds and Launches the Fleet

There are several reasons given for the United States declaring war on Great Britain, among which the upper Great Lakes region figured prominently. Great Britain had violated American sovereignty by refusing to surrender western forts as promised in the Treaty of Paris, and to help them defend their holdings, they were providing arms and goods to Native Americans. American imperialists, on the other hand, were intent on having the British expelled entirely from the continent.

Because of the great natural barrier that is Niagara Falls, Canada was geographically split in two. Lower Canada was accessible directly from the Atlantic Ocean by the Saint Lawrence River and Lake Ontario, and until the War of 1812, the British freely plied those waters. Upper Canada was accessible by a continuum of this system, but by difficult portage around the falls; otherwise, access could only be from the Ohio River tributaries rising in the North. It was clear to both combatants, control of the Old Northwest and Upper Canada would require access to and control of Lake Erie. For control of Lake Erie, warships would have to be built above Niagara Falls. Presque Isle Bay at Erie, Pa. was the American choice for construction of Oliver Hazard Perry’s fleet as its excellent natural harbor offered protection from the frequent sudden storms that blow up on shallow Lake Erie, and because the submerged sand bar barrier that all but enclosed the peninsula to the mainland prevented entry by ships of heavy draft.

Notwithstanding the strategic value of its natural harbor and the virtually unlimited supply of timber available for shipbuilding, in 1813 Erie was a lake port com- munity of about 500 people carved out of the wilderness with little manufacturing or shipbuilding capabilities. Therefore, all manufactured products from nails to sails had to be brought from at least as far as the nascent iron-making town of Pittsburgh, and for armament, from as far as Philadelphia. From Pittsburgh what followed was a difficult 120 mile traverse up the Allegheny River to French Creek, to Le Boeuf Creek at Waterford, then a fifteen-mile portage to Erie. Six ships were built in Erie, including Perry’s two largest ships, the brigs Niagara and Lawrence, and all were completed by late spring 1813.

While British Commander Robert H. Barclay’s fleet could not challenge Perry during the building of the fleet due to the sandbar that gated the channel entrance to Presque Isle Bay, there was much concern that British infantry could march overland from either west or east to attack and destroy the fleet before it ever put to sea. To counter this threat, Perry appealed to General Mead, 16th Pennsylvania Militia Division commander, based in Meadville on French Creek:

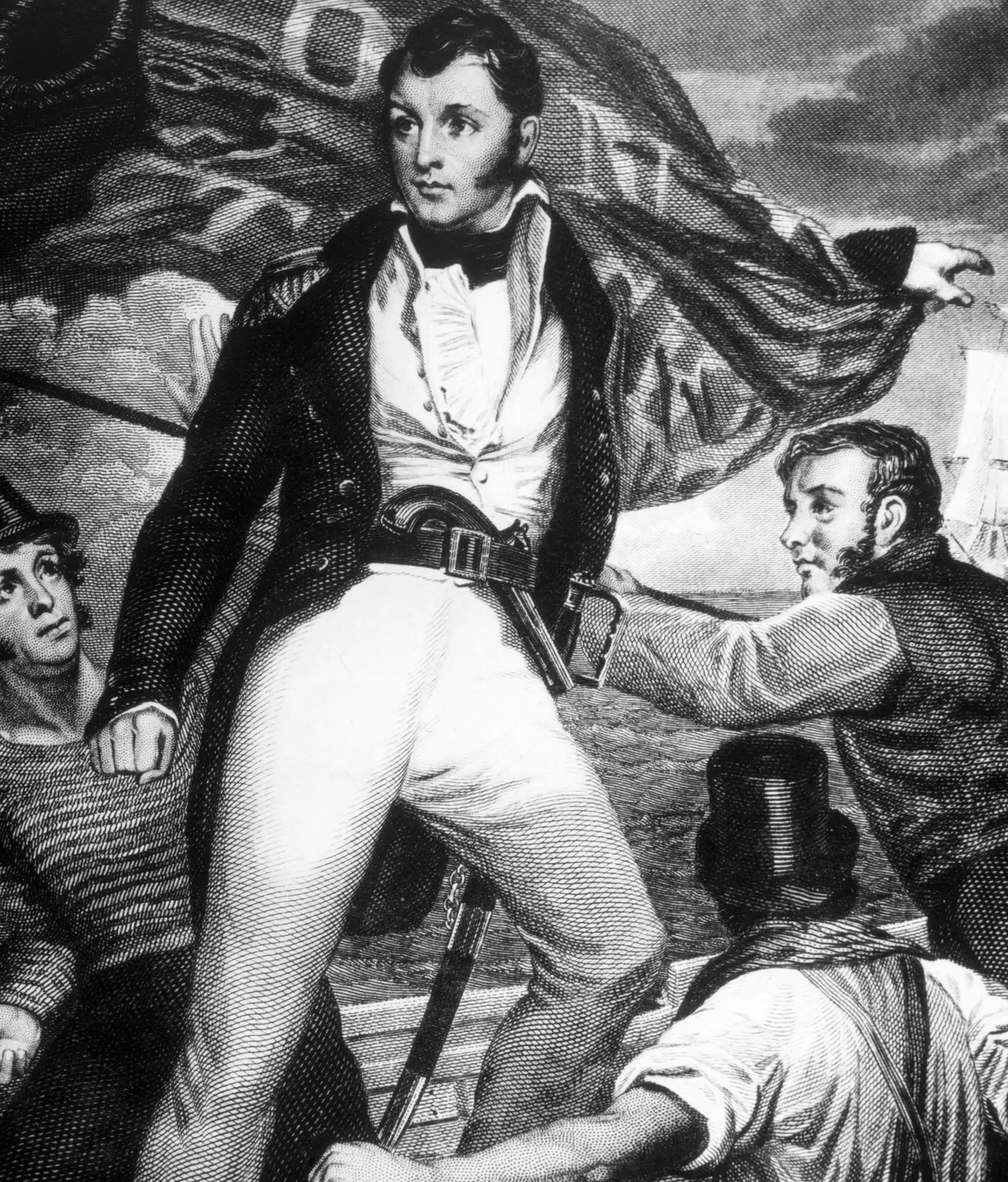

Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry during the Battle of Lake Erie, 1813

While British Commander Robert H. Barclay’s fleet could not challenge Perry during the building of the fleet due to the sandbar that gated the channel entrance to Presque Isle Bay, there was much concern that British infantry could march overland from either west or east to attack and destroy the fleet before it ever put to sea. To counter this threat, Perry appealed to General Mead, 16th Pennsylvania Militia Division commander, based in Meadville on French Creek:

Erie (Penn) April 16, 1813.

Sir,

I am this moment informed that power is vested in you to call out the militia for the defense of this place. You doubtless are acquainted that there is a number of vessels of war building here, and that there is no force to protect them. The Navigation is now nearly open between this and Malden and from the importance to the enemy to destroy those vessels, we may confidently expect they will attempt it. Should they succeed it will be an everlasting disgrace to the country as well as an irremediable loss. If you feel yourself at liberty to order on one hundred men, it would in my opinion add much to our security.

Very Respectfully

I am Sir, O.H. Perry

Com. Of U.S. Naval Forces on Lake Erie

Major General David Mead

Therefore, in the spring of 1813 the 16th Division under General David Mead was called upon to protect the shipyard at Erie while Perry built and readied his fleet for battle. Mead’s response in broadside (presumably) and in the Crawford Messenger (Meadville) newspaper article, if not immediate, was a masterpiece of propaganda:

Citizens to Arms!

Your state is invaded. The enemy has arrived at Erie threatening to destroy our navy and the town. His course, hitherto marked with rapine and fire wherever he touched our shore, must be arrested. The cries of infants and women, of the aged and infirm, the devoted victims of the enemy and his savage allies, call on you for defense and protection. Your honor, your property, your all require you to march immediately to the scene of action. Arms and ammunition will be furnished to those who have none, at the place of rendezvous near to Erie and every exertion will be made for your subsistence and accommodation.

Your services to be useful must be rendered immediately. The delay of an hour may be fatal to your country in securing the enemy in his plunder and favoring his escape.

DAVID MEAD

Maj. General 16th D.P.M.

July 20, 1813

Over the Bar

Erie was not under invasion, for the overland threat never materialized. But Mead’s appeal was effective and the 16th Division turned out. It is unclear why there was such a long-time gap between Perry’s 16 April request and Mead’s 20 July response. No record exists of a timely reply from Mead, nor do the Pennsylvania Archives show muster roles (payment records) before the 20 July call-to-arms from Mead. Mead’s action occurred after the fleet was seaworthy but still vulnerable to land attack inside the peninsula. The 20 July date coincides with Perry’s plan to put to sea and engage Barclay. One may speculate that Mead stood ready to respond after Perry’s 16 April request and would have had ample time to muster his troops should the British begin an overland march, but because planting season was imminent the farmer soldiers were kept home so as not to miss the critical planting season, fundamental to their existence.

What Perry needed after 20 July, however, was assistance in getting his brigs over the sand bar. The sand bar was a barrier that worked two ways, at once both a protective gate and a prison gate. What helped make Presque Isle Bay one of the only secure sites in which to build a fleet on enemy held Lake Erie now created a major tactical problem – Barclay could have his way with Perry as Perry struggled to get the two brigs over the bar. Perry wrote another letter to Mead:

U. States Sloop of war

Lawrence, off Erie,

August 7, 1813

Sir – I beg leave to express to you the great obligations I consider myself under for the ready, prompt and efficient service rendered by the militia under your command, in assisting us in getting the squadron over the bar at the mouth of the harbor, and request that you will accept, sir, the assurance that I shall always recollect with pleasure, the alacrity with which you repaired with your division to the defense of the public property at this place, on the prospect of an invasion.

With great respect,

I am. Sir,

Your obedient servant,

O.H. Perry.

Major General David Mead Pennsylvania Militia, Erie.

Commander Perry expressed his gratitude to General Mead for his “… defense on the prospect of an invasion” indicating the clear threat of an overland invasion existed for the duration of Perry’s sojourn in Erie and was arguably prevented from happening by the strong local threat potential of Mead’s Division, even if not actively on duty. Perry also thanked Mead for his assistance in clearing the bar, which was only nine feet below the surface at the channel entrance. Using camels, or floats lashed to both sides of the hull, raising a ship required significant manpower provided courtesy of Mead’s militia. It is a curiosity of history that Barclay was not present while Perry lie exposed, allowing Perry to escape to the open sea to do battle.

From 20 July through mid-August, when Perry was finally clear of the bar, Mead’s 16th Division was on site, including 230 officers and men of the 133rd Regiment under LTC Samuel Gowdy.

The Battle of Lake Erie

Perry was in need of both sailors and marines to man the ships, so the militia again stepped up to fill the void. Pennsylvania volunteers would soon find themselves engaged in the most important and bloodiest sea battle of the war. Details of this pivotal battle are beyond the scope of this work, however, the service of the militia on the ships under Perry’s command was honored by the Government of Pennsylvania with silver “Perry” medals which bear the tribute: “TO (name of soldier engraved) IN TESTIMONY OF HIS PATRIOTISM AND BRAVERY IN THE NAVAL ACTION ON LAKE ERIE SEPTEMBER 10, 1813”. These metals were issued only to Pennsylvania residents who saw action in the battle, and approximately 39 were struck.

Perry’s final letter to Mead, written six weeks after the Battle of Lake Erie and two weeks after the Battle of Thames, where Harrison defeated British General Henry Proctor and Tecumseh’s Indian Confederacy:

The Battle of Lake Erie, September 10, 1813, lithograph by Nathaniel Currier

Erie, October 22, 1813

Dear Sir – It may be some satisfaction to you and your deserving corps, to be informed that you did not leave your harvest fields in August last, for the defense of this place, without cause. Since the capture of gen. Proctor’s baggage, by gen. Harrison, it is ascertained beyond doubt, that an attack was, at the time, mediated on Erie; and the design was frustrated only by the failure, in gen. Vincent, to furnish the number of troops promised and deemed necessary.

I have the honor to be,

Dear Sir, Your obedient servant,

O.H. Perry.

Major General David Mead, Meadville,

The Battle of Lake Erie was pivotal in allowing America to regain control of Detroit and access to the Northwest frontier. That no shots were fired in anger during their land service belies the point of a home guard, for Perry was unmolested while building and launching his fleet. Perry’s expression of gratitude is an acknowledgement of the value of the militia in both preventing a land invasion and in serving as marines during that famous battle.

Copyright © 2017-2024 by David H. Hanes